The year is 1785.

It would be three years before the U.S. Constitution is ratified, and another two before George Washington would be sworn in as the first U.S. President. Europe was in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, King George III was King of England, and tension leading to the French Revolution was building.

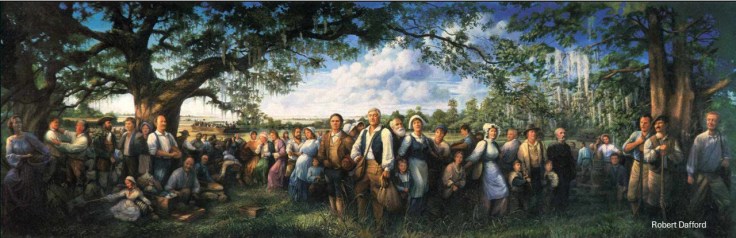

On August 15 of that same year, my 4th great-grand-father Alexis Mathurin Daigle, arrived in the Port of New Orleans aboard “La Bergere,” a 300-ton French merchant ship sponsored by Spain to transport settlers to its newly acquired Louisiana territory. Twenty-two-year-old Alexis, an engraver, was listed as traveling with three orphans, presumably his younger siblings. Upon disembarking after a 93-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean from Nantes, France, he was provided an axe, shovel, meat cleaver, hoe, and hatchet. Apparently, this was standard issue by the Spanish government to help newly arrived settlers bolster its population and provide a buffer against British expansion in the area. Those implements must have been useful, because three years later, he had settled about 50 miles southwest of New Orleans along Bayou Lafourche and was married to a woman named Marie Levron. (WikiTree)

Growing up, it made sense to me that my ancestors came from France since my grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ primary language was French, specifically Cajun French. It was some time later that I learned France was not just the country of origin of my ancestors, but also a waypoint on their journey to Louisiana. My Cajun heritage actually started in a colony known as “l’Acadie” (pronounced la-kah-DEE) New France, in what is now the Canadian Maritimes (eastern region of Canada comprised of the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island). What?! It’s really cold up there!! With my extreme aversion to being even slightly chilly, how could I have descended from people who survived in an area where winter temperatures typically range from 14oF and 28oF?! I’ve got to see this place for myself! Oh, and there’s also bucket-list motorcycle riding up there? What a great excuse for a two-wheel trip to Canada!

Why Canada?

The French government wanted to establish a colony, and create a “New France,” in what is now the Canadian Maritimes, in order to profit from the lucrative fur trade and to expand French influence in North America. The original expedition, led by Pierre Dugua in 1604, landed on St. Croix Island with the intent to discover a “Northwest Passage” that would serve as a shortcut for commerce with the Orient. After half of the men died of illnesses during the first winter, the St. Croix location was abandoned and a new colony was established the following year at a more favorable site – Port Royal on the Bay of Fundy, in present-day Nova Scotia. (Acadian Culture in Maine)

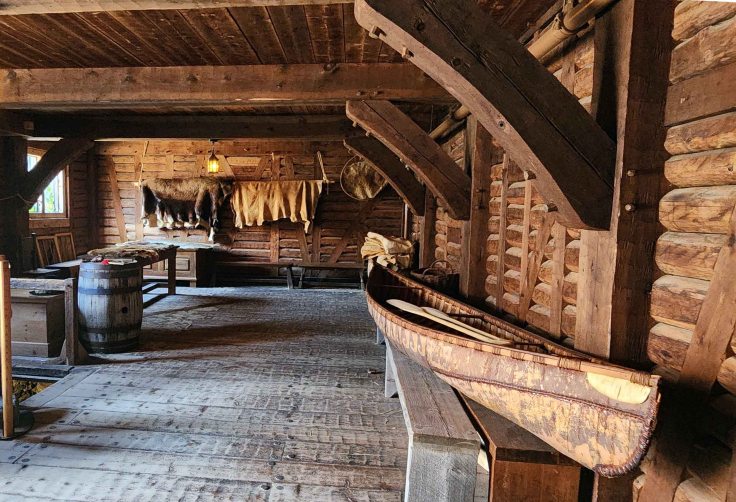

My heritage tour began at the birthplace of Acadian culture, Port-Royal National Historic Site in Nova Scotia. A “reconstruction of the Habitation, one of the earliest European settlements in North America where Samuel de Chaplain lived in 1605.” The Annapolis River Basin was given the name Port-Royal and is where the French continued contact with the First Nation of Mi’kmaq (pronounced MIG-mah) and established trade. The Mi’kmaq-French alliance was crucial to the survival of the newly arrived French traders and the establishment of l’Acadie colony. Economic exchange and alliances against enemies (specifically, the British and other Indigenous peoples) fostered a partnership between the two groups, versus a subjugation of one group by the other (seemingly evidenced by the Mi’kmaq’s sharing of survival techniques and cultural exchanges). This respectful relationship facilitated the expansion of a trading post to a full-blown colony. Though there are two origin stories for the name “l’Acadie,” the most plausible theory is that the name is derived from a Mi’kmaq word rendered in French as “cadie,” roughly meaning a “fertile area.” (UofMaine) The English version of l’Acadie is Acadia.

Life in France in the 1600s was filled with hardships of famine, disease, and heavy taxation for the working class. Several fishermen, farmers, and trappers looking for a better life were recruited from coastal regions of France to populate the growing Acadian colony. The official religion of France in the 1600s was Roman Catholicism, though limited rights were granted to the minority Heugenots (French Protestants) until the middle of the century. The Catholic immigrants who would populate Acadia (Heugenots had to convert to Catholicism once in New France) may have been trying to escape continued tensions between the two religions in addition to seeking a life with better opportunities. (UofKentucky, Wikipedia, MeseeProtestant)

Born in France, my 10th great-grandfather, Oliver Daigre (D’Aigre/Daigre evolved to Daigle by the third Acadian generation) arrived in Port Royal, the original settlement of Acadia in New France, sometime around 1663, at roughly 20 years of age. Though his place of birth is unknown, the French surname D’Aigre signifies a person that comes from the town of Aigre in Charente, France – approximately 50 miles from France’s western coast. I could find no records to verify it, but Oliver may have been an engagé, or indentured servant, as that was an effective method of recruiting young immigrants at the time. An engagé was a male, typically single and in his early twenties, who received, room, board, clothing, and a small salary, from which he would reimburse his employer for passage to Canada, in exchange for signing a 36-month contract of servitude. Many engagé returned to France at the end of their contract, but a small percentage stayed to make a life for themselves in New France. (Rootsweb, French-Canadian Geneologist)

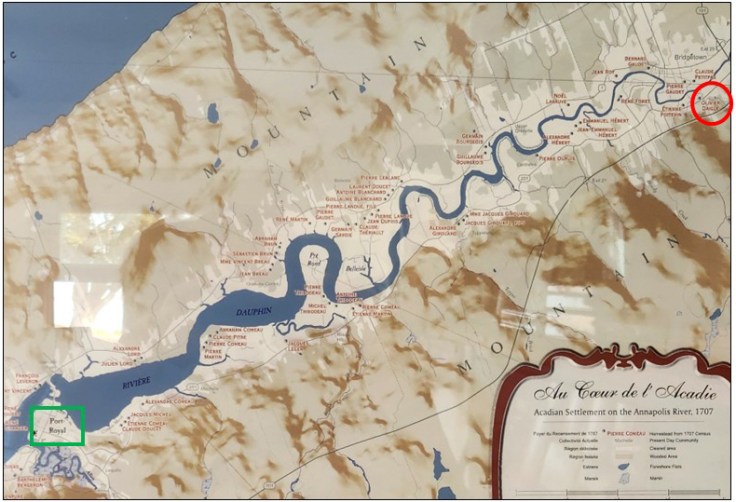

Of the 392 people counted on the 1671 Port Royal census, Oliver is listed as a 28-year-old laborer married to Marie Gaudet, aged 20, with three children (they would go on to have a total of 10 kids). On the census, he is reported to have “two acres of land under cultivation, a team of oxen, and 6 pairs of sheep.” A hard working farmer trying to provide for his family, there’s no way he could’ve imagined that his descendants would number in the tens of thousands over the generations, many of whom would contribute to the unique Cajun culture now associated with south Louisiana. (Rootsweb, WikiTree)

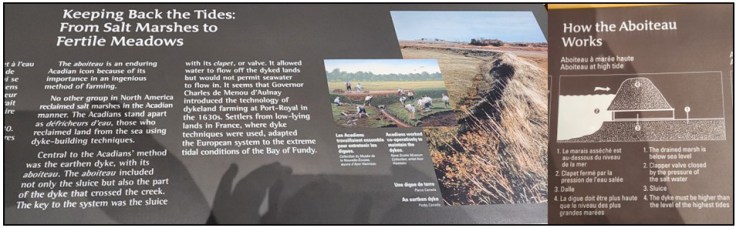

One of the reasons the Mi’kmaq likely let the Acadians settle in their ancestral grounds is due to the Acadians’ approach to land development. Instead of clearing forests vital to Mi’kmaq hunting grounds, they reclaimed coastal salt marshes to create fertile farmlands. Their creation of a system of dykes that allowed water to drain out of marshes while preventing seawater from flowing back in, was key to avoiding conflicts over resources with their First Nation partners. Over time, this innovative land reclamation project was so successful that it had created a “great meadow,” or Grand Pré in French.

So, how did Alexis Mathurin Daigle, the great-great-great grandson of Oliver Daigle, end up settling in Louisiana, via France, instead of staying in Acadia? What happened to the three generations between the two?

Find out in Part 2: Le Grand Dérangement.

** NOTE: This synopsis of my ancestry is my interpretation of secondary sources, not primary.