My heritage tour ride through the Canadian Maritimes in August provided many glimpses into the life of my ancestors when the area was known as l’Acadie/Acadia. In Part 1, I introduced y’all to the first generation of Daigles (Daigre at the time), starting with Oliver Daigle immigrating to Acadia in 1663, and to his great, great, great grandson Alexis Daigle settling in Louisiana in 1758. What happened in the 95 years, three generations, and over 2000 miles separating the two? Keep reading to find out, and click HERE to get up to speed by reading Part 1.

By the mid-1700s, the population of Acadia had grown from its original inhabitants of approximately 400 people to 13,000, with settlements spread across the present-day Canadian Maritimes. Though the French had a strong long-term alliance with the Mi’kmaq, they did not recognize them as a sovereign people with a right to own property. They encroached upon their territory, though they did not pursue large-scale territorial expansion as the British would later do. French colonial policy, based on papal decrees known as the “Doctrine of Discovery” granted European nations the “right” to claim sovereignty and ownership over lands inhabited by non-Christian peoples throughout the world. All of North America was considered free land for the taking by white Christians (specifically only Catholics in the case of the French colonies), which the Acadians did through royal grants, through the Seigneurial System, through indentured servitude with colonial governments and private individuals, and through physically reclaiming fertile marshlands, not already inhabited by other Europeans, from the sea with dikes.

The region of Acadia around the Bay of Fundy switched hands between the French and British at least six times as the two imperial powers struggled for dominance in North America. In 1713, the tug of war ended when Britain gained permanent control over Nova Scotia through the Treaty of Utrecht. Though the Acadians were considered subjects of whichever country held power at the time, they considered themselves Acadian – North American people who spoke French, not French people living in North America. Their daily lives were mostly untouched by the ruling government until 1755. The Daigles, like most Acadians, “tended farms, raised their families, and founded new communities along the Bay of Fundy” while troops from the two countries waged their battles without direct Acadian involvement. (Jobb)

Four Generations of Daigles

1st Generation: Oliver Daigle (abt. 1643-bef. 1685)

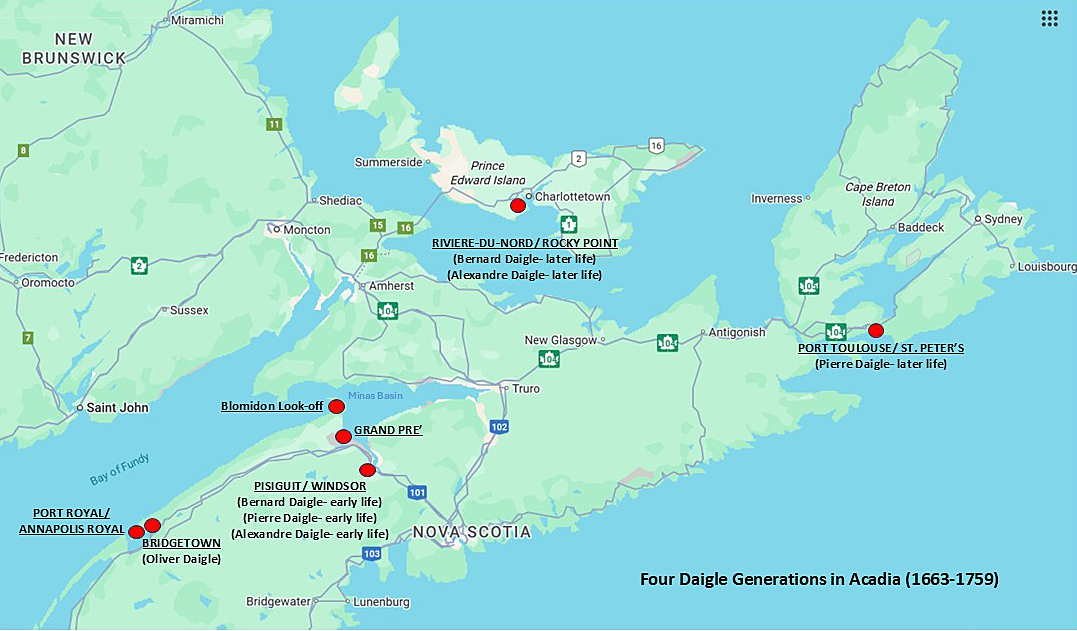

After immigrating from France around 1663 to Acadia in New France, Oliver married Marie Gaudet and built their home across the Annapolis River from her family’s settlement, in what is present-day Bridgetown, Nova Scotia. They had seven sons and three daughters. They tended their farm and raised their family until Oliver died some time in his late thirties or early forties (between 1681-1686). Marie remarried and died at 88 years old in 1734. (WikiTree, Assoc. of Daigle Family)

2nd Generation: Bernard Daigle (abt. 1670-1751)

Oliver and Marie’s son, Bernard, lived with his mother, stepfather and six siblings on their farm in Port-Royal, which was “5 arpents [acre] of land with 13 cattle, 9 sheep, and 8 hogs.” In 1691, he married Marie-Claire Bourque (Bourg) and grew their family to 13 kids. They settled in Pisiguit (present-day Windsor, Nova Scotia), about 10 miles from his parents. Some time after Marie-Claire died, and when he was 56 years old, Bernard moved across the Northumberland Strait to Port-La-Joye, île Saint-Jean (present-day Rocky Point, Prince Edward Island), where he died in 1751 around 80 years old. (WikiTree)

3rd Generation: Pierre Daigle (abt. 1696-1759)

Eighteen-year-old Pierre, one of the sons of Bernard and Marie-Claire, born in Pisiguit, married 15-year-old Madeleine Gautrot (Gautreaux) in 1715. They settled in the same town as Pierre’s parents and had nine children. Records show that at the age of 53, Pierre got remarried to Marie Testard in 1750, presumably after Madeleine passed away. Pierre and Marie lived in Port Toulouse, île Royale (present-day St. Peter’s, Cape Breton Nova Scotia), with five children from her first marriage.

NOTE: There is a lot of confusion at this level of my family tree due to several like names, so this is my best interpretation based on WikiTree and FamilySearch.

4th Generation: Alexandre Daigle (abt. 1730-bef. 1779)

Like his father’s first marriage, Alexandre met and married a woman from Pisiguit, Elisabeth Granger, around 1750, but within a year, they are listed as residents of Riviere-du-Nord, Isle St. Jean, (Prince Edward Island) which is near where his grandfather Bernard is reported to have died. He is listed as a married, 22-year-old ploughman with a young son and only 1 ox, 1 cow, and 1 sow; “they have made no clearing, having been there only a short time.” Unfortunately, Alexandre would not have time to establish his homestead before politics would interrupt his plans. (WikiTree)

Le Grand Dérangement

Life for all Acadians would change in 1755. When forced to swear an oath to the British King after the treaty of 1713, the Acadians would only do so conditionally: they promised to remain neutral in exchange for being exempt from fighting against France and the Mi’kmaq. This defiance to unconditional allegiance was allowed until 1755, when France’s hold on surrounding territories threatened England’s position in Nova Scotia. The British power now demanded the Acadians swear total obedience to the crown, with no conditions. Their continued refusal, along with the discovery of a handful of Acadians taking up arms against the British at Beaubassin (Fort Beauséjour), resulted in what came to be known as Le Grand Dérangement, or the great upheaval – the forced expulsion of approximately 11,500 Acadians between 1755 and 1764.

The British-orchestrated expulsion started in August 1755 when the belligerent Acadians at Beaubassin were arrested and gathered for deportation. On September 5, 1755, the men of Grand-Pré and Pisiquid were summoned by British officials. In light of the recent events in Beaubassin, the men assumed they were going to be reminded of their oath of neutrality and life would go on as usual. However, once 300-400 Acadian men and boys were packed into the church of Saint-Charles-des-Mines in Grand Pré, and another 183 at Fort Edward in Pisiguit, the doors were locked, and they were read the King’s proclamation for deportation. It was too late for unconditional oaths or negotiations, the wheels to destroy Acadian cohesion and culture were now in motion. (Jobb)

What followed was the systematic confiscating of property, burning of settlements to avoid leaving refuge for stragglers and escapees, and the deliberate separation of families to prevent reunification and resistance. By purposefully, and forcefully, dispersing families and communities to different countries and British-controlled territories, existing social structures were destroyed and it was more difficult for deported Acadians to regroup and form a unified resistance against the British authority. Separating families and communities and dispersing them amongst British colonies (and England) was intended to persuade the disheartened Acadians to give up their French loyalties (including the French language and Catholicism) and learn to assimilate and adopt British culture and loyalty. The brutal deportations continued throughout all Acadian settlements in British-controlled Nova Scotia and New Brunswick for 8 years, eventually spreading to French-controlled territories in île Royale (Cape Bretton Island, Nova Scotia) and île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island).

Having both moved to the French-held islands of Cape Bretton and Prince Edward from the Bay of Fundy area of Acadia to escape British rule, and thus considered French subjects, the two living generations of my direct Daigle ancestors were deported in 1758-1759 to France instead of British-held territories. Alexandre and his family were shipped to Boulogne, France, while his father Pierre and his family were deported to St-Malo, France, 300 miles apart. The much longer and dangerous voyages across the Atlantic to France, versus along the eastern U.S. coast to British colonies like earlier deportations, resulted in a higher death rate from disease, starvation, and drowning due to shipwrecks. I can’t imagine how miserable a north Atlantic crossing must’ve been during winter in the mid-1700s. Though Pierre and Marie Louise survived the winter sea crossing, they died less than a month after arriving in St-Malo, France in January 1759, and within weeks of each other. (WikiTree)

Pierre’s son, Alexandre, his wife Elisabeth Granger, and one son, were amongst the 179 survivors of a winter trans-Atlantic journey, arriving in Boulogne, France the day after Christmas in 1759 (300 miles north of where his father and step-mother were dropped off). (WikiTree)

To give you a sense of the devastating effects of the deportation on individual families, I will use my ancestor Pierre as an example. From what I can glean from secondary sources, the following is my synopsis. (WikiTree, RootsWeb)

- 4 of Pierre’s 9 children, and 17 of his 26 nieces and nephews, died at sea from disease, illness, or shipwreck

- Pierre’s 12 siblings were dispersed and deported to Quebec, England, possibly Massachusetts, and France (with one shipwrecked in the Azores, Portugal never making it to France)

- Pierre, his wife, 1 of his children, and 2 of his siblings died within 2 months of reaching St-Malo, France

For those who survived the deportation, no matter where they were sent, they were mostly unwelcomed refugees to already struggling communities.

Next up, Part 3: Making a new life as refugees.

Hi my name is Chelsea Daigle and I’m almost positive we’re related after reading this post. I’d really like to connect with you and have a chat if you’d like. My instagram is @spiritual.nomad.life

thank you for writing this all out I really enjoy reading it.

LikeLike

I’m a Daigle and My Father grew up in Fort Kent Maine by Oscar Daigle Farms (St. John & Fort Kent Border. His direct decedents for several generation s had a dairy farm in Baker Brook NB across the river which is now Oscar Daigle Farms. I’m sure we’re related. Direct descendant of Simon Joseph Daigle written on the Madawaska-Acadian Cross.

LikeLike